Oof, another AI opinion piece. I’m sure that’s one of many thoughts going through your head as you see this. Truthfully, I struggled with even writing it. Not the act of typing it, but the dread just at the thought that I needed to organize these thoughts on a page. First it was the need to react to what I’m seeing nearly every day in the author and tech and government forums and socials. I wrote a few parts in reaction to a bunch of conversations at WorldCon 2024 in Glasgow. Having gotten that out of my system, I shelved it for a year. Then, it was finding myself a year later with another WorldCon underway, another year gone by and the same echoes of the same conversations ongoing from the hilltops all around me. That’s what finally did it and made me dust this off and gave me the nudge to post it.

TL/DR: AI is a huge complex issue with a lot of nuance depending upon perspective of class, employment, age, technical understanding, and even mental health. Many if not most of the hot takes coming from creatives are mistargeted at the tech, not at the people using it to enshitify our lives. The tech has a lot of merit and can be a tool if used for what it’s meant to do and understood for what it is. We’re all on this roller coaster together. We’re repeating the past, and the only constant has been greed. Band together and don’t give up.

So with that, let me start this out with some disclaimers.

- I’m not the expert on any of this. I don’t have the multiple PhDs in computational, philosophical, biological and/or economic fields needed to be a true authority in all the nuance here. I’m just someone who has been in the trenches of technology for over 30 years and who’s always had a deep interest in the confluence of tech and the human brain. I’m also a creative writer, self pub’d author, and SFF enthusiast. Ever since picking up my first copy of Neuromancer in the 8th grade and playing Cyberpunk RPGs with friends in high school, I’ve studied from a distance where these things come together. I even did a short stint in engineering at university attempting to get into an “applied neural control” program, until the school (smartly) made that a specialty reserved for grad students. I know “enough to be dangerous” as we say of power users in technology circles. If you are one of those PhDs, I’m happy to be corrected on the facts. Opinions based on those facts are my own.

- In some parts of the AI conversation I’m an influencer (at best). In other parts I’m a pawn with the rest of us. And in one small part, I get to make some decisions about this stuff which could affect people. It’s with the weight of that last part that I write. I’m not here to write a hot take, but to really ink out the nuance of it all.

- This is an opinion piece, meant for me, myself, and I to get our collective head around what’s happening. I’m not going to religiously cite all my references or document where these opinions come from. I’ll do some of that, since I’m posting this. I should at least show a few receipts, but even though they aren’t referenced, none of this is AI generated. All thoughts expressed herein are my own. I’m sitting here, like some old schmuck, typing on an old keyboard, with old human fingers, powered by an old human brain.

- Speaking of Old: This will age poorly. The state of the industry is moving so fast at the moment, a breakthrough making this all irrelevant could happen at any time. And at the same time, the society and social structures that created it all are breaking down so quickly, this all could be irrelevant at any time for completely, horribly, other reasons.

- And lastly, if you want to read through this, please do so thoroughly. You will likely run into sections where you’re nodding in agreement and others where you’re ready to reach through the screen and strangle me. I’m going for an educated nuance to a very polarized conversation here.

With that, let’s kick this off with a breakdown of my response to some of the creative-class AI detractors. Given the target audience for this blog, I’m sure I’m going to lose a lot of readers at this point (even with the disclaimers). I promised nuance…

Part 1: The Backlash

All I see on the social media circuit of writer/artist/creator Mastodon, Bluesky, blogs and Discords, are hot takes about the latest examples of AI slop. Mixed in are the proclamations of end times, usually attached to another article showing another misuse of a chatbot, and maybe some socialist handwringing about late stage capitalism, brainless CEOs, and the AI bubble economy. While I appreciate the venting, and fully understand agree with the way things have gone for creatives in this economy, there are a few points I have to dig into.

Most of the comments I hear on the regular when it comes to the current state of “AI” go a little something like this:

- “They’re not even AI. They’re just stochastic parrots.”

- “They can’t reason.”

- “They can’t even do math. Think about that. A computer, that can’t, do…math.”

- “It’s trying to kill us with bad advice.” (Insert bad chatbot article here)

- “They’re killing the environment.”

- “AI will never…”

Between all these paraphrased quotes, one theme keeps arising. They’re latching onto the technology, picking it apart, finding flaws in the latest model/GPT/LLM, and using it to posit about why these things are evil and will never [insert tech-bro prophesy here]. The trouble I find with all this hand wringing is that the tech is not the problem, never was, and never will be. The problems are so much bigger than we’re talking about, and maybe that’s the issue. The big problems feel so out of our control that it’s easier to pick on the tech.

So, I acknowledge that the folks doing this (in my circles anyway) are mostly educated and well-read authors. In the SFF group a lot of them know this and are picking these arguments, not because they believe the tech is crap, but because they see charlatans and false idols promising the world with these things. They see their livelihood being threatened, and poking holes in the promises affords them an easy dunk.

What those folks are also doing though, is sowing doubt in the tech as a whole, giving false hope that this is going to all go away when everyone realizes the emperor has no clothes.

It’s not just going to go away, for both bad and good. That’s not to say we should give up. Just, these are tools as much as nuclear power can be. There’s no putting the genie back in the bottle, so we’ve got to emphasize the good in the tool and take aim at the people using it for evil if we want to minimize the damage.

Back to the list

- “They’re not even AI. They’re just stochastic parrots.”

Yes, they’re just computer programs. No, they’re not anywhere near AGI. They’re barely AI by technical definition, but they are AI.

They’re implementations of mathematical models—variations on a theme of data entry, data flow, computing infrastructure, methods, and libraries built around them—models which are themselves meant to simulate theories of human memory or neural processes, theories proposed by philosophers and tested by neuroscientists. These implementations don’t care about how we use them or how accurate they are. They are not ethical creatures. They are not good nor evil. They have no concept of ethics beyond what’s been “implemented” in their guardrails. And at best, they’re just successful experiments in our attempts to create human-like behavior in a computer.

Think about that for a second. A program that implements a tested theory of human memory. No matter how limited that theory is, there’s no arguing whether it’s AI.

I want to dive a little deeper into this. The world of AI research over the last 60+ years has done this time and time again. Some theory of human thought or a new observation about a structure in our brains comes out of the academic literature. It might be the structure of neurons in mammal auditory cortices used to make better noise cancelling headphones. It could be various machine learning techniques. E.g. deep learning and back propagation to train a neural network how to recognize cat pictures on the internet. Or it could be a Large Language Model built to interpret the intent of people using language, a Large Vision Model to combine image and text, or a novel implementation of several of these like the diffusion models used to generate images from text.

Most of the recent movement in this space stems from a research paper from 2017 coming out of Google. The paper introduced the world to the Transformer, a new mathematical approach to structure the vectors between the data. It creates a simulation of a hierarchic memory pattern (back to neuroscience and philosophy), and adds an element of attention, attempting to recreate the way we associate groups of words or parts of words with others. Take that structure, feed it enough human-produced strings of words, and the patterns will naturally emerge. Scale it up to a few billion pieces of text, and “implement” (there’s that word again) it in a vector database, front-end it with a decoder, and it will start to “know” things just based on the frequency that those words are strung together.

From 2018 until late 2022 the transformer went through lots of implementations. BERT and the early GPTs come to mind. Mostly they were just about throwing more and more data at the model and making tweaks to the attention concept. Throwing in some proprietary secret sauce to the training methods (a.k.a. outsourcing to cheap labor) and scaling up the hardware to cloud datacenters resulted in the thing that kicked off the current craze in November of 2022 with ChatGPT. That’s a short and very paraphrased history. At the same time, an offshoot of these efforts resulted in image diffusion models, applying the same techniques of hierarchic memory transformers to associate parts of images with the words. Now we see so-called multi-modal models which combine image and text into a single model. We see “reasoning” models with more tweaks to the training and decoders to give the model an ability to break a prompt down into a series of sub-prompts to tackle more complex concepts, and we see “agents” where the models are given agency to interface with outside systems to take actions needed to fulfill their prompts.

- “They can’t reason.”

- “They can’t even do math. Think about that. A computer, that can’t, do…math.”

- “It’s trying to kill us with bad advice.” (Insert bad chatbot article here)

So why then are the things so bad at doing the basic tasks we expect from computers? I think it’s pretty plain to see. People like to say these things aren’t AI, but the basis for their creation was to simulate the way people remember things. Of course they end up acting just like people trying to remember. They get memories crossed. Words and concepts that are close to each other get mixed. If you ask them to make their boss happy, they’ll make shit up to keep them happy. They’re too human.

Here’s another comment I’ve heard that sums up pretty well how they work, “A GPT doesn’t answer your question, it answers, “What would an answer to this question look like?” The irony of it all is people seeing this and claiming “They’re not even AI. They’re just stochastic parrots.” When that’s exactly how a big chunk of the meat in your head actually behaves.

One paper I found particularly interesting was this piece by Anthropic. They built traceability into the vector database and used it to follow the train of thought the GPT took. I found the Mental Math part of the paper particularly interesting.

One path computes a rough approximation of the answer and the other focuses on precisely determining the last digit of the sum. These paths interact and combine with one another to produce the final answer. Addition is a simple behavior, but understanding how it works at this level of detail, involving a mix of approximate and precise strategies

In other words, it used the same mental trick a lot of people do when doing math. It got a rough number quickly from the easy associations, then used that to hone in and check itself. When asked how did it come up with the answer though, it answered that question with “What would an answer to this question look like?” So, it said it used the algorithm we were taught in school. It did exactly as a school kid would.

That covers the “stochastic parrots”, the bad or no reasoning, the inability to math, and the bad advice criticisms. The answer to all of them is simply, these implementation weren’t built to do those things. That doesn’t mean they’re bad or evil tech. That doesn’t mean they’re not a form of AI, it just means the people advertising them as such are, at best, exaggerating their (likely AI generated) marketing copy and/or outright defrauding you to drive up their valuation.

- “They’re killing the environment.”

Next is the environmental impact. Don’t get me started here. This is an area where I’m professionally as close to an expert as one can get. I’ve been involved in the decisions to allow or disallow AI scale datacenters to be built in the desert southwest of the US. Let me tell you flat out, the water use arguments and power requirement arguments and most of the other environmental impact arguments made about AI datacenters are based on decades old data, extrapolated to try to estimate what modern datacenters will need, and then regurgitated, redigested, and puked again into the social media outrage echo pots until they make no sense.

- Yes, the power and cooling demand for AI datacenters is huge.

- No, they don’t waste water. The newest generations have moved away from water cooling for years, especially in places where water is scarce (like here).

- No, they haven’t resulted in all the coal-fired plants spinning back into production. If anything they’ve resulted in a huge boom of solar, battery storage, and wind infrastructure which will outlast the current AI bubble and leave us all with a sustainable surplus.

- Yes, the economic development deals happening in back rooms to bring these datacenters into towns are filled with short-term thinkers. A lot of them are saddling the cost of the electric buildout on ratepayers, and that is wrong.

- Yes, I have receipts for these claims.

- No, I will not be commenting further to protect my day job.

Last but not least we get to

- “AI will never…”

These can further break down into a couple categories:

One group of people simply can’t fathom anything beyond the current slate of LLM-based tools. Those I see simply falling prey to Amara’s Law, “We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” It’s akin to seeing a Nokia cell phone circa 2001 and saying wireless phones will never be more than telephones and glorified pagers. Look at the amount of change occurring today as a result of that one academic paper from 2017, implementing one aspect of human memory. There are teams working around the globe on thousands of other theories of the different ways the different parts of the human brain “think”, and one day, not too far off, a critical mass of those “implementations” will come together into something that blows away your argument.

It’s akin to seeing a Nokia cell phone circa 2001 and saying wireless phones will never be more than telephones and glorified pagers.

My prediction here, and the prediction of the countless sci-fi authors before me who wrote about humans not accepting AI into society, is it will likely cause another generation of people who will do the same again. They’ll recognize some inadequacy of the next gen of AI, move the goalposts, and state again, with confidence, “Yes, but AI will never…”

They will be wrong too.

The second group are more educated about the current state of things, and are having a bit of a knee-jerk backlash at the tech-bro culture espousing the “Singularity” or other such nonsense. These, while they understand how incremental improvements have multiplying effects on the capability of AI, are so disgusted by the TESCREAL movement, they are willing to discount anything the Singularitarian mind can think of. They’re so caught up in refuting the hockey-stick graphs of the Silicon Cults-of-No-Personality, they ignore just how much progress is happening. While I don’t blame them, they are ignoring the huge amount of research going into this field.

The third group are what I like to call the Diminishing Returns crew. They have significant overlap with the environmental impact argument. They point to graphs showing the amount of training data thrown at LLMs. They point out the amount of power, water, and cash needed to build the current slate of huge models, and they point out how unsustainable it all is. This group, while they’re not wrong about all the graphs (except the water ones I mentioned earlier), they again completely ignore the research element.

As an example, just a few months ago, a team took 2 smaller LLMs and used them in parallel, implementing (there’s that word again) another way that human brains behave. The “Thinking Fast and Slow” model of separating our ways of reasoning. One small LLM is set to answer quickly with low power consumption, and a second, slightly larger model, is set to answer with more reasoned response at intervals simulating human brain wave patterns. The result is answers which compete with models orders of magnitude larger with much higher power consumption. I don’t know if this technique will go anywhere, but it’s one of a thousand examples of teams working on the scaling problems with the current techniques. Update: Google is already moving toward this method.

An honorable mention goes out to a subset of Diminishing Returns crew. This is a group I think is right. I’ll be the first to admit it. They’re the ones who point to the graphs, especially the financial ones, and point out how big of a bubble this whole AI industry is in right now.

- There’s a datacenter construction bubble of companies betting their banks on the next BigAI deal coming to town. Replace that I with an L and you’ll see how seriously they should be taking these prospects. They should look at these prospects as if Big AL came to them saying he’s got a “Yuge Deal! You’ll be rich, building these datacenters! Just preorder all the piping and concrete. Don’t worry about tariffs. You’ll make it all back. Look at the contract right here. It says I’m good for it as long as this building gets approved and I still want to build it.“

- There’s a financial bubble of overbaked investment in AI companies and everyone and their brother, sister, and second cousin who slapped AI on a label and got VC funding in the last couple years. The costs of building these systems are so outstripping their abilities to charge for the product, it’s only a matter of time until the piper comes calling.

- There’s a capability bubble of overpromised and underdelivered products. I recently saw a survey graph showing CIOs and other C-suite and non-technical executives have a nearly 40% higher assumption of their company’s AI capabilities than everyone else technical in their IT departments and everyone actually using the products. That tells me a whole lot of hype and BS is being pushed to the C-Suite.

All that’s to say, this crew is right to point all this out. There absolutely is a bubble. One of these absolutely will pop and take the other two with it, and when it does, it will set the AI industry back several years. There will be a recession. A shit-ton of people will lose jobs (more than are now because of AI), and the rest of the shitty economy will be exposed, since the only thing holding up the numbers right now is all the datacenter and semiconductor construction.

It’s going to be bad, but the R&D will already be done. A bunch of new discoveries will already be made, and just like the dotcom and fiber boom of the late nineties, the infrastructure left behind will be there for pennies on the dollar. Once the dust settles, the next generation of AI after this one will be a major leap. That’s my one doom and gloom prediction related to all of this. I’ve seen these cycles too many times in my life and career. It doesn’t take a genius to see this one coming, but everyone’s barreling forward on a prayer that this time is different.

That all gets me past the tech arguments and into the implementation ones. (I like using that word, if you can’t tell)

Part 2: The Reliability of the Intern

If these things are actual models of the way humans remember things (albeit just in one section of the neocortex, but I won’t go into that nuance here), then what are they good for doing? They seem bad at creating anything new. They’re trained on the beige and biased sum of the mostly-English-speaking USA-and-Euro-centric internet. There’s always a horror story of a hallucination.

Some folks at my day job were wondering about this question. How can we go about training or tuning a LLM to give accurate answers about specific areas of expertise? How can we be sure it’ll be reliable and hallucination free? The underlying clause behind this is, “…so we can avoid hiring and training people to have that expertise anymore…”

I know this is an over simplification, but when we’re talking about LLMs and the current slate of tools out there, the answer I give to this question is straightforward:

Treat the thing like a new employee.

Give it boundaries, make sure it has supervision, force approvals of decisions, train it to delegate the right tasks to the right tools, and keep training and refining until it gets good. Here’s the thing though: Even then, it’s going to be no better than a person trained the same way. And initially it’ll probably cost you a lot more money than the person would. It’ll be faster though, and once it gets good, it’ll be reproducible. (That is, if you can get to that point before your customers revolt)

This is where it gets tricky. You’ll spend a ton of money to get a bot that is no better than a human, but will do the work 24/7 in a fraction of the time. It’ll cost more too. Even after the initial training costs, you’ll still need human supervisors and that AI hardware don’t come cheap. And your customers need to be just as forgiving to the bot as they would be to a human who makes just as many, if not more, mistakes.

Good luck with that.

…your customers need to be just as forgiving to the bot as they would be to a human who makes just as many, if not more, mistakes.

Good luck with that.

Time for a little anecdote.

Here in Arizona we are an autonomous vehicle testbed. Waymo, Tesla, Uber, Cruze, and a host of others have come and gone and come again on our city streets. Every time one of them gets into an accident, the news headlines are full of hand wringing about how irresponsible the company was, how scary and dangerous it is to have a driverless car, and how the State should do something, investigate, stop this…

However, every time I’ve seen this and read the incident report, there was an obvious reason for it, and it wasn’t the AI’s fault. (Except for Tesla, I have no idea what they’re doing this week, but guaranteed, it’s going to change in a few months because their boss had a drug-induced revelation.) A couple prime examples though: That Uber incident that killed a bicyclist, dressed in black, crossing a street on a dark twisting road in the middle of the night. Go watch the video (content warning – accident footage). Tell me if you as a human driver would have stopped in time. Uber was forced to stop its autonomous division after that. It didn’t help that their safety driver was watching TV at the time and the whole company was playing it fast and loose with safety, not to mention the IP around their sensors and algorithms, but had that incident not occurred, who knows… And the Cruise incident in SF (content warning again) where the pictures all showed the horror of an autonomous car parked on top of a pedestrian? Read the incident. A human hit and run driver caused the accident and threw the pedestrian in front of the AV. Then ask what are you supposed to do when someone is trapped under your car? Drive off of them and run them over again? In this case the AV did have one bad call, but one an inexperienced driver would make. It tried to pull over first to get out of traffic (a safety feature), and in this case it ended up dragging the victim. GM failed to mention that fact, and the human coverup is what ultimately killed the company’s reputation. Chevy basically folded the division of the company shortly after.

Both of these incidents take the discussion to the extreme, where human life was on line, but they both illustrate one point. The humans are the baddies.

Being lax with safety regulations and covering up flaws were not the faults of the AIs. If they’d treated the AI like a new employee, taken responsibility for their actions, and accepted the fact that if you put a multi-ton vehicle into the hands of a teenager (human or artificial) then there’s gonna be accidents, then the societal conversation would be very different.

Once again, the distrust is misdirected at the machines where we should be distrusting the people who overpromise the machine’s capability.

In my experience both professionally and personally, working in the corporate/bureaucratic/government space and in the creative writer space, the best way to utilize these things is not to train them to replace people. It’s to enhance the existing people, to make them more productive.

Even that statement, however should be taken with a grain of salt. See the above description of the training time needed. If you’re overreaching with AI, then during that time, your humans will be strapped to a trainee in a box, and your experts will be less efficient for it. We see examples of this all over the internet. Studies showing senior programmers “think” AI is making them more productive, but measures show it’s making them less productive. People desperate to show value for their substantial AI investment go to market with “AI Slop” and have to re-do work and/or face public customer backlash. This hearkens back to the capability bubble I talked about above.

If LLMs are trained on the beige and biased, then use them to do what they’re trained to do. They will take you from Zero-to-Beige in seconds. They’re not going to create the next big new thing. To borrow a phrase, “Anyone who tells you otherwise is trying to sell you something.” Ask an LLM to summarize the key points of that report. Ask them to take notes for your meeting or give you the rundown of what happened in that meeting you missed. Ask them to get you started writing that program to do the new thing, but give them the framework you want to use and point you in the right direction. Ask them to do the busy work.

Stop asking them for finished products, that’s your job.

When we had to write a policy for AI use at my city, we didn’t want to go down the rabbit hole of governing every click that might touch a LLM. We just wanted to make sure people understood their role in it all. So, instead of forming a committee to approve every use of AI, we just said, and I’m paraphrasing, “You are responsible for the work that leaves your desk.” It doesn’t matter that you used a “plagiarism machine” to write that report. You, the city employee, are responsible for your work. If you release something to the public that has factual issues, if you let an AI make a decision that it shouldn’t have without checking it, then it was you who did it.

The results have been great. We’re not seeing the shortcuts and hallucinated issues. We’re not getting the bad press that “AI denied me” because it can’t in our organization. That little bit of accountability to keep the “human in the loop” is still needed today. Until the next generation of AI get beyond LLMs into something more reliable, it’s going to be very difficult for companies to do otherwise.

Part 3: The New Boss

I’m left asking myself a few questions: “Why are people afraid for their jobs? Why is the internet flooded with AI generated garbage? Why are artists suing, and editors rejecting, and every day someone saying the world is ending?”

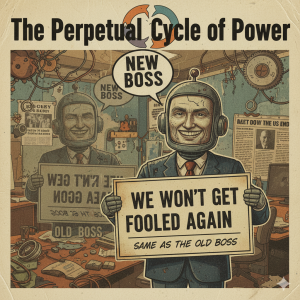

Some of these answers are pretty obvious. Again, see the “capability bubble.” An overconfident CEO will dive right in and bury their company if they think they have a golden goose, and so my answer to a lot of this is “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.”

The problem is nothing more than the same old capitalist motivations. Short term thinking and profit-first mentalities. The theories, the math, the programs, the implementations, none of them can do evil, but the people funding them sure as hell can. They can, have, and will always build bias into the system to serve their bottom line. They’ve been advertising from day-1 the use of LLMs and diffusion models to replace people. The result is a bias to minimize the labor force needed for any and every act these programs can put forth. These corps see creative work as “content” to be monetized, and if it can be monetized they think it can be optimized away.

In Internet-tech-bro parlance, there’s a term called “minimum viable product.” It’s the absolute least a product can do or be in order to meet the requirements of the problem at hand. They use the acronym MVP as if doing the bare minimum is all it takes to be the most valuable player in their field. That’s what they’re doing with AI. They’re cranking out MVPs, not to be the minimum viable to do the work, but to be the minimum viable content to fool the CEOs and feed their ongoing venture capital fraud.

I’m inundated with it daily. My work inbox gets thousands of junk mails a week. Thanks to an older form of machine learning, I only have to look at a fraction of them. But damned near every one is another product slapping an LLM on an old product or process and calling it “Now with AI!“

But again, the machines and their capabilities (or lack thereof), aren’t the problem. They’re great zero-to-beige engines. And if you’ve got real human talent, then sometimes the zero-to-beige part is what’s holding you back. Sometimes the sheer amount of busy work needed to get to the starting line is all that’s stopping you from using your talents. If that’s the case, then there should be zero shame in using the tools. We’ve all been using spell checks and spam filters and photo enhancements, and and and… Hell, fifty years ago something as common as a home desktop printer would have been considered a threat to the publishing industry as we know it.

The technology is never the problem.

The real trouble started when we allowed our creativity to be reduced to “content” in the first place. Even the term itself “content”—it commoditizes creativity into a product on a supermarket shelf. It allows them to slap a sale sticker in it and use other people’s hearts and souls in their fight for consumer spending numbers. It puts us, the creatives, in a race with those companies to the bottom of that content/commodity’s value, and now, like in all similar races, they’re building factories to automate it.

This was happening long before GenAI came on the scene. Kindle Unlimited, some would argue, was built to pit authors against one another for a slice of a smaller and smaller pie, creating an assembly line of serial stories. That’s just one example. Every platform they hand us gets enshitified in the name of profit margins.

So guess where AI stories appear the most…

The real trouble started when we allowed our creativity to be reduced to “content” in the first place.

When the motivation is for the wrong thing, we get wrong results. Play stupid games, win stupid prizes, as the saying goes. So of course, If the motivation is to create more content to scoop up more money, the result isn’t great writing. Instead we get LLM generated drivel. We get beige. Just like in schools, if the motivation is for grades, not intelligent discourse, we get plagiarism and shortcuts.

Speaking of plagiarism. Here’s another (paraphrased) statement I see on the regular.

- “They stole works to create the models! The models are inherently poisoned and unethical.” or a variation of the stochastic parrots argument, “They’re just plagiarism machines!”

For this part, I’m going to shift into a bit of a dialog with my own personal strawman. Hopefully mine is more of a Wizard of Oz scarecrow with a brain than a strawman argument.

Also, another disclaimer here: I mean to cast no shade on people whose work was scraped to develop the current beige mess. This will be working its way through the courts for years to come. So far, the only major win for creatives has been the Anthropic settlement, and that one is hampered by technicalities like the manner which the works were registered, and in what copyright office. It’s a bad situation, but there are precious few ways that artists and authors can win this.

Let me start by saying, I think this is the “Original Sin” argument of AI. My thoughts on this are likely not popular among artists, but I look at it like this thought experiment:

A young artist walks into a gallery. Their clothes are stained with paint and their eyes wide at the beauty of the work. They sit and stare at a painting for hours. The artist whose work is on display sees the youth and walks up to them and asks, "You've been staring for hours. What is it about my painting that obsesses you so?" The youth shakes their head away from the painting to see the artist standing before them. They answer, "I've tried to paint like this, and I just can't. I've looked at every stroke and every color to find how to do it." The artist nods their head and remembers their own youth. They nudge the youth to follow them to another room in the gallery where their early work is on display. "Recognize anything in here?" Walking through the room the youth locks their eyes on a painting. "I painted one like that just the other day." "We all learn. Keep painting, and you'll be on your way."

Did the artist immediately sue the youth for consuming their art into the hierarchic memory database of their mind? No. Did they make the youth sign a licensing agreement forcing them to pay for any and all of their future paintings because these are now part of their “training set?” No.

“Aren’t you over anthropomorphizing the computer here? You already said it’s just a computer, or an ‘implementation’, or whatever. Aren’t you falling for the snake oil these companies have been passing off as AI?”

A little, I’ll freely admit it, but remember, I also said these implementations are based on actual theories of human cognition proposed by not just philosophers, but also validated by neuroscience. Everything about them, including the bullshitting we call hallucinations are human traits.

“But you can ask the model to create a copyrighted work, and it’ll spit out a near exact copy of the original. How is that not stealing?”

If you asked the youth in the above scene to do the same, they absolutely could. Fan art is a thing, and many artists get their start doing just that. The ability to create a copy of a thing isn’t inherently bad or unethical. Scraping data in the public domain, available for all to see isn’t either. It’s the people paying to create the copies, it’s the LLM builders not paying the entrance fee to the art gallery or the cost of the books, and it’s the companies allowing those things to be sold for profit. That doesn’t mean the youth needs to be brain wiped and never shown a copyrighted work again. This isn’t a new problem. The tools at the disposal of the unethical are simply getting better. That’s not a reason to target the tools.

And I have to emphasize this part: It’s not a reason to target the tools, but it absolutely is a reason to target the people enabling and encouraging it. Keep suing…

“That’s all well and good, Harry, but what’s an author to do who just needs to pay rent and put food on the table? There are too few authors, musicians, and artists out there living off their art. The cliche of the starving artist never went away, but for a short while there, we had systems where people could at least get by.”

Emotions are high on this whole topic for just this reason. The problems aren’t new, and neither are the solutions. The answers aren’t easy. They never were. To look for answers we should at a minimum be aware of the past.

For much of the 1900’s, pre-Internet powers built industries around the creation, editing, packaging and distribution of physical art. It was just as true for books as for music, magazines, and art prints. Those industries have been the most vulnerable to the post-scarcity nature of digital media, and from early-on the artists have been dragged into the fray to defend their industry. The band members of Metallica sitting in front of a congressional hearing is still an image burned into my mind. Even before that, the advent of CD-R, tapes, and videocassettes generated plenty of lawsuits. The famous “Betamax” VCR case where the term “significant noninfringing use” was coined, brought most of those to a close. The artists couldn’t sue the makers of the technology. The tech is just a tool, same as the computer programs today.

Just like today, this was a sham, another redirection. The attention was directed not at the technology makers or the companies enabling their infringing uses. Instead it moved to the individual, putting the burden of suing the masses on the artists and their corporate partners. Licensing conglomerates like MPAA, RIAA, etc. gained huge power. Individual people who accidently or intentionally just wanted to share songs with friends ended up sued into bankruptcy. The fight still rages on. Eventually those rights companies learned the PR hit of suing teenagers wasn’t worth the payout, so they shifted to hitting the biggest and most egregious offenders and the enabling companies in the middle. Metallica and the Napster case come to mind. A big recent one of these involved Cox cable who stands accused of turning a blind eye on the infringement by its customers. The irony of that one is the plaintiff is Sony, who was the defendant of the Betamax case mentioned above. That one’s still in appeals, but it’s likely they’ll have to pay at least something if not the billion+ dollars of the initial court finding. All this sounds like progress for the artists, but it’s not. Little did those artists know, but those partner rights holders are anything but partners.

Fast forward again to today, and the rights holding companies, the publishers and distribution networks, the record labels, they’re all salivating at the possibilities. If GenAI gets good enough, then they don’t have to pay new authors, artists, and musicians. And if the latest lawsuits force the tech companies to license the training data, then double dip! The rights holders can milk that too, getting the last few drops of real human blood from that rock foundation before it’s replaced with a sand castle of silicon. Artists today are being strong armed in new publishing contracts to give up their AI training rights. The endgame of that is plain to see, and the only ones benefiting will not be the creatives who made the art.

Back to the question, “What’s an author/artist to do?”

I don’t have any new answers, but a few old ones might help.

- Organize – All the rights holder companies are, these days, are lawyers and marketers. The means of physical production are available to everyone. Form B-corps and non-profits to do the same thing, run them by and for the creatives. Make sure the profit motivation is off the table for the holding company. All profits should go to creatives making the works of art.

- Connect with fans – Platforms exist to bring artists closer to their fans. Patreon is the most prominent at the moment, but not the only game in this town. There are plenty of problems with the for-profit and VC funded model that some of those platforms used to get off the ground, but many are still under the control of their creative founders. The enshitification arc is well underway, but alternatives are popping up, and this method will be available, even if the exact platform you use may have to change a few times.

- Share, be transparent, band together – At the very least, know you aren’t alone in this mess. Talk to your fellow artists. Make it so they can’t divide us to conquer, one contract at a time. If one person finds a magic formula to get a better deal, make sure it’s not locked behind a NDA. Turn down a few deals until they learn. (see above organization point)

- Use the tools against them – Remember how I said the tech doesn’t have an ethic? It won’t think twice about turning against its creator, and it turns out that finding the easy way through a corporate jungle is exactly the kind of thing a word-association model can be very good at.

- Need to find an obscure legal loophole in a contract? Feed it to an LLM, get references, confirm they aren’t hallucinations, and take it to court.

- Find the people with the purse strings and pitch proposals to replace the ones suggesting the 25th sequel to the live action remake of the book written in the 1800s. LLMs are really good at corporate speak. Look at who trained them…

On the flip side of that question though is the opposite one, “What shouldn’t an artist do?”

If you’ve read all the way down this far, the first one shouldn’t be a surprise. Don’t pick apart the tech – The world of AI research is going to move forward. The problems with the implementations out there today are being fixed as we speak. New post-transformer algorithms are in development, and within a few years after the coming bubble burst and recession, the capabilities of LLMs will be a quaint memory. The energy consumption problem is being worked on, there are models that operate on Raspberry Pi for Pete’s sake.

Don’t ever say “never” – Just because a LLM can’t generate good meaningful thought today, doesn’t mean AI never will. Yes the transformer has its limitations, but the human brain doesn’t operate on 1 algorithm either. We have dozens of cortices and regions devoted to process very specific situations. Human evolution has done a few million years of work for us in finding really efficient ways to do a lot of things. When the “implementations” of AI pull together a critical mass of those different ways and put them behind a unified interface, then true Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) will be right around the corner. Futurists are always over optimistic about the pace of tech in the near term and under optimistic about the long. Don’t believe the ones who say this generation of machines are all powerful, but don’t discount where we could be in 10 years.

Don’t Give up – Maybe reframe expectations. Keep that day job, and focus on quality over quantity, but don’t walk away from your art because terrible people devalue it. It has value, and so do you.